Snake + Gopher = <3

By Amit Lavon

Introduction

When working in Python, it sometimes makes sense to implement parts of the program in a static, high-performance language. Go can be a great choice for that because it is fast, simple and cross platform.

This tutorial started as a cheatsheet I wrote for myself. In my research I work mostly in python. However, since I work on large amounts of data, I needed a heavy-duty language for some of my more demanding analysis tasks. That’s when I started exploring the possibility of exporting parts of my analysis routines to Go.

In order to implement the advice shown here you will need Python 3, a Go compiler, and GCC (on Windows use MinGW). The code examples are available as runnable files on github.

There exist other ways to cross-call Go from Python, such as extension modules and SWIG. Each has its own pros and cons. I chose ctypes because it has no additional dependencies and it is easy to learn.

This tutorial is based on my own experience, so it might contain suboptimal practices or even mistakes. Your feedback and ideas are welcome!

Hello World

Let’s start with the bare minimum.

import "C"

import "fmt"

//export hello

func hello() {

fmt.Println("Hello world!")

}

Build:

# Windows:

go build -o hello.dll -buildmode=c-shared hello.go

# Linux:

go build -o hello.so -buildmode=c-shared hello.go

lib = ctypes.CDLL('./hello.so') # Or hello.dll if on Windows.

hello = lib.hello

hello()

Then run:

> python hello.py

Hello world!

>

Congrats!

Let’s break it down:

- The Go code uses regular Go logic, but exports its function for external

use with the

//exportdirective. - Building with

-buildmode=c-sharedcreates a C-style shared library. - Python loads the shared library and accesses the exported function.

Primitive Input and Output

Here we introduce some basic arguments and return values. Let’s start with an example.

import "C"

//export add

func add(a, b int64) int64 {

return a + b

}

lib = ctypes.CDLL('./primitive.so')

add = lib.add

# Make python convert its values to C representation.

add.argtypes = [ctypes.c_int64, ctypes.c_int64]

add.restype = ctypes.c_int64

print('10 + 15 =', add(10, 15))

Run:

> python add.py

10 + 15 = 25

>

To pass input and receive output to/from a Go function, we need to use ctypes’s

argtypes and restype attributes. They do 2 things:

argtypesguards the function by checking the arguments before calling the library code.- Using these attributes tells Python how to convert the input Python values to ctypes values, and how to convert the output back to a Python value.

You can find the mapping between C types and Go types in the generated .h

file after you compile your Go code with -buildmode=c-shared.

DANGER: Some types change sizes on different architectures. It is generally

safer to use sized types (int64) here than unsized types (int).

Arrays and Slices

We are now entering the zone of unprotected memory access. While Python and Go are generally memory safe, working with raw pointers could end up in buffer overflows and memory leaks.

Make sure to read this section through to learn how to handle pointers safely.

import "C"

import "unsafe"

// Returns the squares of the input numbers.

//

//export squares

func squares(numsPtr *float64, outPtr *float64, n int64) {

// Wrap the pointers with Go slices (pointing to the same data).

nums := unsafe.Slice(numsPtr, n)

out := unsafe.Slice(outPtr, n)

// If using Go < 1.17.

// nums := (*[1 << 30]float64)(unsafe.Pointer(numsPtr))[:n:n]

// out := (*[1 << 30]float64)(unsafe.Pointer(outPtr))[:n:n]

for i, x := range nums {

out[i] = x * x

}

}

lib = ctypes.CDLL('./arrays.so')

squares = lib.squares

squares.argtypes = [

ctypes.POINTER(ctypes.c_double),

ctypes.POINTER(ctypes.c_double),

ctypes.c_int64,

]

# Building buffers from arrays is more efficient than

# (ctypes.c_double * 3)(*[1, 2, 3])

nums = array('d', [1, 2, 3])

nums_ptr = (ctypes.c_double * len(nums)).from_buffer(nums)

out = array('d', [0, 0, 0])

out_ptr = (ctypes.c_double * len(out)).from_buffer(out)

squares(nums_ptr, out_ptr, len(nums))

print('nums:', list(nums), 'out:', list(out))

Run:

> python squares.py

nums: [1.0, 2.0, 3.0] out: [1.0, 4.0, 9.0]

>

In order to work with lists we need to convert them into C arrays. The way to

do it is to create an array using (ctypes.my_type * my_length)(1, 2, 3 ...).

The faster way to do it is to use the array library as demonstrated above.

See the benchmarks section for more info about their performance.

In Go you can cast the C-like pointer to a slice (that still points to Python’s memory), see the demonstration above. This way you can utilize Go’s syntax while working with Python buffers.

Output lists are the tricky part. You cannot return a Go pointer when using CGo,

that will result in an error. Instead you can allocate a C pointer from Go using

C.malloc() and return that. However, that pointer is not garbage-collected

so unless you implement a way to deallocate those, you will have a memory leak.

My recommendation for safely returning arrays from Go is to either pre-allocate them in Python and pass them as arguments to Go, or to generate the arrays in Go and wrap them in a safe-finalizing struct (see structs section).

Summary of Dangers

- Returning Go pointers to Python. Error.

- Returning C pointers from Go to Python without explicit deallocation. Memory leak.

- Losing the

ctypesreference while Go code is still running (like when takingctypes.addressofand dumping the pointer object). Possible segmentation fault.

Strings

Strings work pretty much like arrays in terms of memory management, so everything related to arrays applies here too. Below I discuss some convenience techniques and some pitfalls.

//export repeat

func repeat(s *C.char, n int64, out *byte, outN int64) *byte {

// Create a Go buffer around the output buffer.

outBytes := unsafe.Slice(out, outN)[:0]

buf := bytes.NewBuffer(outBytes)

var goString string = C.GoString(s) // Copy input to Go memory space.

for i := int64(0); i < n; i++ {

buf.WriteString(goString)

}

buf.WriteByte(0) // Null terminator, important!

return out

}

lib = ctypes.CDLL('./string.dll')

repeat = lib.repeat

repeat.argtypes = [

ctypes.c_char_p,

ctypes.c_int64,

ctypes.c_char_p,

ctypes.c_int64,

]

repeat.restype = ctypes.c_char_p

# Reusable output buffer.

buf_size = 1000

buf = ctypes.create_string_buffer(buf_size)

result = repeat(b'Badger', 4, buf, buf_size) # type(result) = bytes

print('Badger * 4 =', result.decode())

result = repeat(b'Snake', 5, buf, buf_size)

print('Snake * 5 =', result.decode())

Run:

> python repeat.py

Badger * 4 = BadgerBadgerBadgerBadger

Snake * 5 = SnakeSnakeSnakeSnakeSnake

>

Strings are passed by converting a Python string to a bytes object (typically

by calling encode()), then to a C-pointer and then to a Go-string.

Using ctypes.c_char_p in argtypes makes Python expect a bytes object and

convert it to a C *char. In restype, it converts the returned *char to a

bytes object.

In Go you can convert a *char to a Go string using C.GoString. This copies

the data and creates a new string managed by Go in terms of garbage collection.

To create a *char as a return value, you can call C.CString. However, the

pointer gets lost unless you keep a reference to it, and then you have a

memory leak. To return strings from Go, use the same practices as with arrays.

If the output pointer was given by Python, Go can return it and Python will automatically make a bytes object out of it. See the demonstration above.

Summary of Dangers

- Returning a

C.CStringwithout keeping the reference for future deallocation. Memory leak. - Not appending a null terminator at the end of the output string. Buffer overflow when converting to Python object.

- Not checking output buffer size in Go. Buffer overflow or truncated output.

Array of Strings

Passing an array of strings can be done with a snippet by Stack Overflow user habnabit.

func goStrings(cstrs **C.char) []string {

var result []string

slice := unsafe.Slice(cstrs, 1<<30)

for i := 0; slice[i] != nil; i++ {

result = append(result, C.GoString(slice[i]))

}

return result

}

def to_c_str_array(strs: List[str]):

ptr = (ctypes.c_char_p * (len(strs) + 1))()

ptr[:-1] = [s.encode() for s in strs]

ptr[-1] = None # Terminate with null.

return ptr

Numpy and Pandas

Numpy provides access to its underlying buffers using the

.ctypes.data_as(ctypes.whatever) syntax. With pandas you can use the .values

attribute to get the underlying numpy array, and then use numpy’s syntax to get

the actual pointer. This way you can change the array/table in place.

import "C"

import "unsafe"

//export increase

func increase(numsPtr *int64, n int64, a int64) {

nums := unsafe.Slice(numsPtr, n)

for i := range nums {

nums[i] += a

}

}

lib = ctypes.CDLL('./numpypandas.so')

increase = lib.increase

increase.argtypes = [

ctypes.POINTER(ctypes.c_int64),

ctypes.c_int64,

ctypes.c_int64,

]

people = pandas.DataFrame(

{

'name': ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie'],

'age': [20, 30, 40],

}

)

# First we check the type.

ages = people.age

if str(ages.dtypes) != 'int64':

raise TypeError(f'Expected type int64, got {ages.dtypes}')

values = ages.values # type=numpy.Array

ptr = values.ctypes.data_as(ctypes.POINTER(ctypes.c_int64))

print('Before')

print(people)

print('After')

increase(ptr, len(people), 5)

print(people)

Run:

> python table.py

Before

name age

0 Alice 20

1 Bob 30

2 Charlie 40

After

name age

0 Alice 25

1 Bob 35

2 Charlie 45

>

It is important to check the type of the array before passing it to your Go function. Go asserts the data is of a certain type, and that might not be true. The data may be of a different numeric type (int<–>float), a different size (int64<–>int32), or of type object.

Another thing to keep in mind is that Pandas copies tables when selecting rows.

For example, if we have a DataFrame called people, then

people[people['age'] < 40] will return a copy of people. Therefore passing

the copy to Go will not affect the original table.

Calling Python to Allocate Memory

Returning dynamically allocated arrays from Go to Python can be tricky, as the memory needs to be freed manually. Can we find a safer way to do that? Well, yes!

Python can allocate memory buffers using the array library. These arrays are freed using Python’s regular garbage collection. But how can Go ask Python to allocate arrays on the go? Answer: we’ll pass a callback to Go that would allocate a python array and return a pointer to that array’s buffer.

Confused? So am I.

Let’s break it down. First, we’ll make an allocator function in Python.

# A function that receives an array type string and a size,

# and returns a pointer.

alloc_f = ctypes.CFUNCTYPE(ctypes.c_void_p, ctypes.c_char_p, ctypes.c_int64)

arrays: list[array] = []

@alloc_f

def my_alloc(typecode, size):

arr = array(typecode.decode(), (0 for _ in range(size)))

arrays.append(arr)

return arr.buffer_info()[0]

Using CFUNCTYPE allows us to use a Python function as a C callback.

The typecode parameter is used to choose the array’s data type.

Notice that the function keeps the generated arrays in a list. We have to keep them alive until the Go function returns, in order to keep them from being garbage-collected.

What happens in Go?

We’ll start with some C weirdness, since Go can’t call the callback directly.

/*

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdint.h>

typedef void* (*alloc_f)(char* t, int64_t n);

static void* call_alloc_f(alloc_f f, char* t, int64_t n) {return f(t,n);}

*/

import "C"

Next, for convenience, we’ll make a wrapper around this, so the rest of our code can be in plain Go.

// Calls the Python alloc callback and returns the allocated buffer

// as a slice.

func allocSlice[T any](alloc C.alloc_f, n int, typeCode string) []T {

t := C.CString(typeCode) // Make a c-string type code.

ptr := C.call_alloc_f(alloc, t, C.int64_t(n)) // Allocate the buffer.

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(t)) // Release c-string.

return unsafe.Slice((*T)(ptr), n) // Wrap with a go-slice.

}

Now, we can wrap this function with some type-specific functions. Notice that the type-codes are Python’s array type codes.

func allocFloats(alloc C.alloc_f, n int) []float64 {

return allocSlice[float64](alloc, n, "d")

}

func allocInts(alloc C.alloc_f, n int) []int64 {

return allocSlice[int64](alloc, n, "q")

}

func allocBytes(alloc C.alloc_f, n int) []byte {

return allocSlice[byte](alloc, n, "B")

}

And for some extra leisure, a string function.

func allocString(alloc C.alloc_f, s string) {

b := allocBytes(alloc, len(s))

copy(b, s)

}

To put it all together, let’s make a function that reports the square roots of integers up to n.

/*

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdint.h>

typedef void* (*alloc_f)(char* t, int64_t n);

static void* call_alloc_f(alloc_f f, char* t, int64_t n) {return f(t,n);}

*/

import "C"

import (

"fmt"

"math"

"unsafe"

)

//export sqrts

func sqrts(alloc C.alloc_f, n int64) {

allocString(alloc, fmt.Sprintf("Square roots up to %d:", n))

floats := allocFloats(alloc, int(n))

for i := range floats {

floats[i] = math.Sqrt(float64(i + 1))

}

}

func allocFloats(alloc C.alloc_f, n int) []float64 {

return allocSlice[float64](alloc, n, "d")

}

func allocInts(alloc C.alloc_f, n int) []int64 {

return allocSlice[int64](alloc, n, "q")

}

func allocBytes(alloc C.alloc_f, n int) []byte {

return allocSlice[byte](alloc, n, "B")

}

func allocString(alloc C.alloc_f, s string) {

b := allocBytes(alloc, len(s))

copy(b, s)

}

// Calls the Python alloc callback and returns the allocated buffer

// as a slice.

func allocSlice[T any](alloc C.alloc_f, n int, typeCode string) []T {

t := C.CString(typeCode) // Make a c-string type code.

ptr := C.call_alloc_f(alloc, t, C.int64_t(n)) // Allocate the buffer.

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(t)) // Release c-string.

return unsafe.Slice((*T)(ptr), n) // Wrap with a go-slice.

}

# A function that receives an array type string and a size,

# and returns a pointer.

alloc_f = ctypes.CFUNCTYPE(ctypes.c_void_p, ctypes.c_char_p, ctypes.c_int64)

arrays: list[array] = []

@alloc_f

def my_alloc(typecode, size):

arr = array(typecode.decode(), (0 for _ in range(size)))

arrays.append(arr)

return arr.buffer_info()[0]

lib = ctypes.CDLL('./alloc.so')

sqrts = lib.sqrts

sqrts.argtypes = [alloc_f, ctypes.c_int64]

sqrts(my_alloc, 5) # Populates arrays with the result.

print(arrays[0].tobytes().decode(), arrays[1].tolist())

Output:

Square roots up to 5: [1.0, 1.4142135623730951, 1.7320508075688772, 2.0, 2.23606797749979]

Structs

To work with structs, you need to define them both in Python and in C. Exporting Go structs is not possible.

/*

#include <stdint.h>

typedef struct person {

char* firstName;

char* lastName;

char* fullName;

int64_t fullNameLen;

} person;

*/

import "C"

import (

"bytes"

"unsafe"

)

//export fill

func fill(p *C.person) {

buf := bytes.NewBuffer(unsafe.Slice((*byte)(unsafe.Pointer(p.fullName)),

p.fullNameLen)[:0])

first := C.GoString(p.firstName)

last := C.GoString(p.lastName)

buf.WriteString(first + " " + last)

buf.WriteByte(0)

}

class Person(ctypes.Structure):

_fields_ = [

('first_name', ctypes.c_char_p),

('last_name', ctypes.c_char_p),

('full_name', ctypes.c_char_p),

('full_name_len', ctypes.c_int64),

]

lib = ctypes.CDLL('./structs.so')

fill = lib.fill

fill.argtypes = [ctypes.POINTER(Person)]

buf_size = 1000

buf = ctypes.create_string_buffer(buf_size)

person = Person(b'John', b'Galt', buf.value, len(buf))

fill(ctypes.pointer(person))

print(person.full_name.decode())

Since we cannot export Go structs, we define them in C by adding a comment

above the import "C" line. Notice that in Go the struct person is referred

to as C.struct_person. In Python we define an equivalent ctypes.Structure

class that has exactly the same fields.

When it comes to populating struct fields in Go, primitives are quite straightforward. When it comes to arrays and strings, the same limitations as before apply.

Automating Memory Management Using __del__

Setting up a convenient and safe memory management scheme is the last

piece in our puzzle. Using Python finalizers (__del__), we can

conveniently allocate buffers in (C)Go, and have Python free them when the

object is discarded.

This scheme is simple and requires two things: a finalizer function in Go that will deallocate an object’s buffers, and a finalizer in Python that will call the Go finalizer. The Python finalizer will be called automatically when the object’s reference count goes to zero.

/*

#include <stdlib.h>

struct userInfo {

char* info;

};

*/

import "C"

import (

"fmt"

"unsafe"

)

// Generates a data object for Python.

//

//export getUserInfo

func getUserInfo(cname *C.char) C.struct_userInfo {

var result C.struct_userInfo

name := C.GoString(cname)

result.info = C.CString(

fmt.Sprintf("User %q has %v letters in their name",

name, len(name)))

return result

}

// Deallocates a data object.

//

//export delUserInfo

func delUserInfo(info C.struct_userInfo) {

// This print is only for educational purposes.

fmt.Printf("Freeing user info: %s\n", C.GoString(info.info))

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(info.info))

}

class UserInfo(ctypes.Structure):

_fields_ = [('info', ctypes.c_char_p)]

def __del__(self):

del_user_info(self)

lib = ctypes.CDLL('./del.so')

get_user_info = lib.getUserInfo

get_user_info.argtypes = [ctypes.c_char_p]

get_user_info.restype = UserInfo

del_user_info = lib.delUserInfo

del_user_info.argtypes = [UserInfo]

def work_work():

user1 = get_user_info('Alice'.encode())

print('Info:', user1.info.decode())

print('-----------')

user2 = get_user_info('Bob'.encode())

print('Info:', user2.info.decode())

print('-----------')

# Now user1 and user2 should get deleted.

work_work()

print('Did I remember to free my memory?')

Run:

Name: Alice

Description: User "Alice" has 5 letters in their name

Name length: 5

-----------

Name: Bob

Description: User "Bob" has 3 letters in their name

Name length: 3

-----------

Freeing user info: User "Alice" has 5 letters in their name

Freeing user info: User "Bob" has 3 letters in their name

Did I remember to free my memory?

Error Handling

Communicating Go errors back to Python is essential for a complete program flow. To accomplish that, we will create a reusable error type.

/*

#include <stdlib.h>

typedef struct {

char* err;

} error;

*/

import "C"

import (

"fmt"

"unsafe"

)

func newError(s string, args ...interface{}) C.error {

if s == "" {

// Equivalent to a nil Go error.

return C.error{}

}

msg := fmt.Sprintf(s, args...)

return C.error{C.CString(msg)}

}

//export delError

func delError(err C.error) {

if err.err == nil {

return

}

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(err.err))

}

// Checks if a non-negative number is even.

//

//export even

func even(i int64) (bool, C.error) {

if i < 0 {

return false, newError("%v is negative, want at least 0", i)

}

return i%2 == 0, newError("")

}

class Error(ctypes.Structure):

_fields_ = [('err', ctypes.c_char_p)]

def __del__(self):

# We can call del_error with a None err, but this way we can avoid

# the call overhead when it's not necessary.

if self.err is not None:

del_error(self)

def raise_if_err(self):

if self.err is not None:

raise IOError(self.err.decode())

class EvenResult(ctypes.Structure):

# Multiple return values can be grabbed in a struct.

_fields_ = [

('result', ctypes.c_bool),

('err', Error),

]

lib = ctypes.CDLL('./error.so')

del_error = lib.delError

del_error.argtypes = [Error]

even = lib.even

even.argtypes = [ctypes.c_int64]

even.restype = EvenResult

for i in (0, 1, 2, 3, -5):

e = even(i)

try:

e.err.raise_if_err()

except IOError as err:

print('Error:', err)

continue

print(i, 'even:', e.result)

We can use the new Error type in structs and functions with multiple return values (see the example code files).

Performance Tips

The Cost of No-op

The cost of no-op (an empty function call) is a magnitude of 5 us. This is a high price to pay per function call, compared to native function calling. It turns out that CGo has a high call overhead. My measurements show that it applies also when calling Go from native C code, whether the Go code is linked through a dynamic or a static library.

This overhead should be taken into account when designing an API. If each function call has 5 us of Go work, then it is going to spend 50% of its time on call overhead. If each function call has 500 us of Go work, then call overhead will make about 1%.

Reuse Buffers

For calls that repeat many times, if it make sense to, try to allocate your ctypes buffers once and reuse them across repeating calls.

A convenient trick is to allocate the buffer in a function’s closure. It has 2 benefits:

- Design: you can keep the buffering abstract from users of the function (no need to pass the buffer around).

- Memory management: creating the closure function within a local scope (not as a global) allows it to get garbage-collected along with its buffer when no longer needed.

For example:

# The ctypes wrapper for my Go function.

my_function = my_lib.my_function

def my_function_with_buffer(n: int):

buffer = (ctypes.c_char * n)(*([0] * n))

def my_function_with_closure():

my_function(buffer, n)

return my_function_with_closure

def work_work():

my_function_buffered = my_function_with_buffer(1000)

my_function_buffered()

my_function_buffered()

my_function_buffered()

# When the function exits, my_function_buffered is released along with

# its buffer.

Use the array Library to Allocate Arrays / Buffers

As mentioned above (and below under Benchmarks), using the array library to

allocate buffers is faster than the regular constructor of a

(ctypes.type * n) value.

Benchmarks

A few comparisons to illustrate the potential benefit of using Go. All measurements include the overhead of converting values to and from their C representation.

Tested on my personal desktop: Intel i5-6600K, 16GB RAM, Windows 10, Python 3.7.6, Go 1.14.

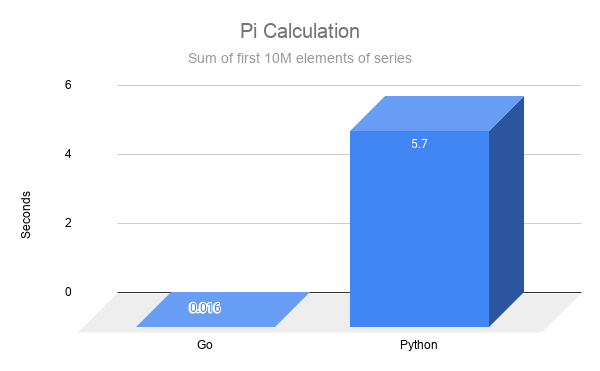

Pi

A simple comparison calculating the number Pi, to get a feeling of how much faster Go can be.

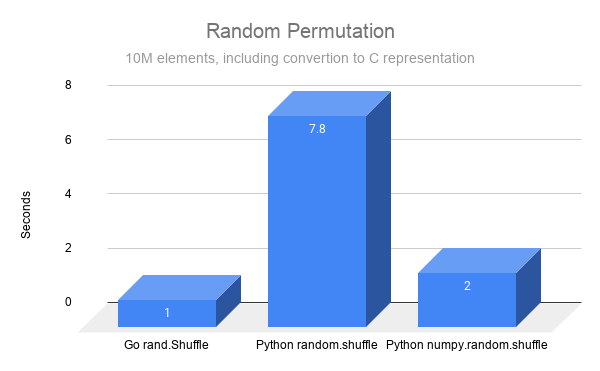

Random Permutation

Comparing a more complex procedure. Notice how using Go can be faster than Python’s builtins.

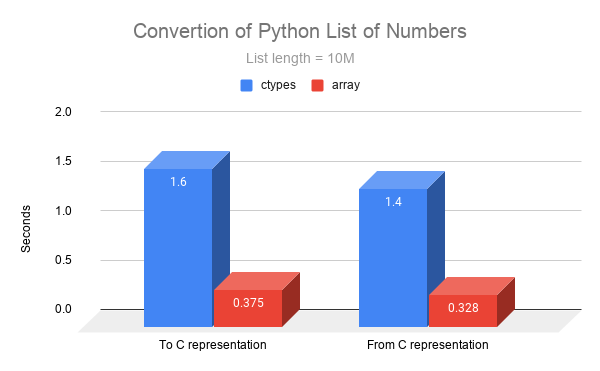

Using array for Conversion

Comparing using the constructor recommended by the ctypes package

documentation, to using array for converting Python values to C values.

# Using ctypes

cvals = (ctypes.c_double * n)(*nums)

# Using array

arr = array('d', nums)

cvals = (ctypes.c_double * n).from_buffer(arr)